Social Credit Prognostications

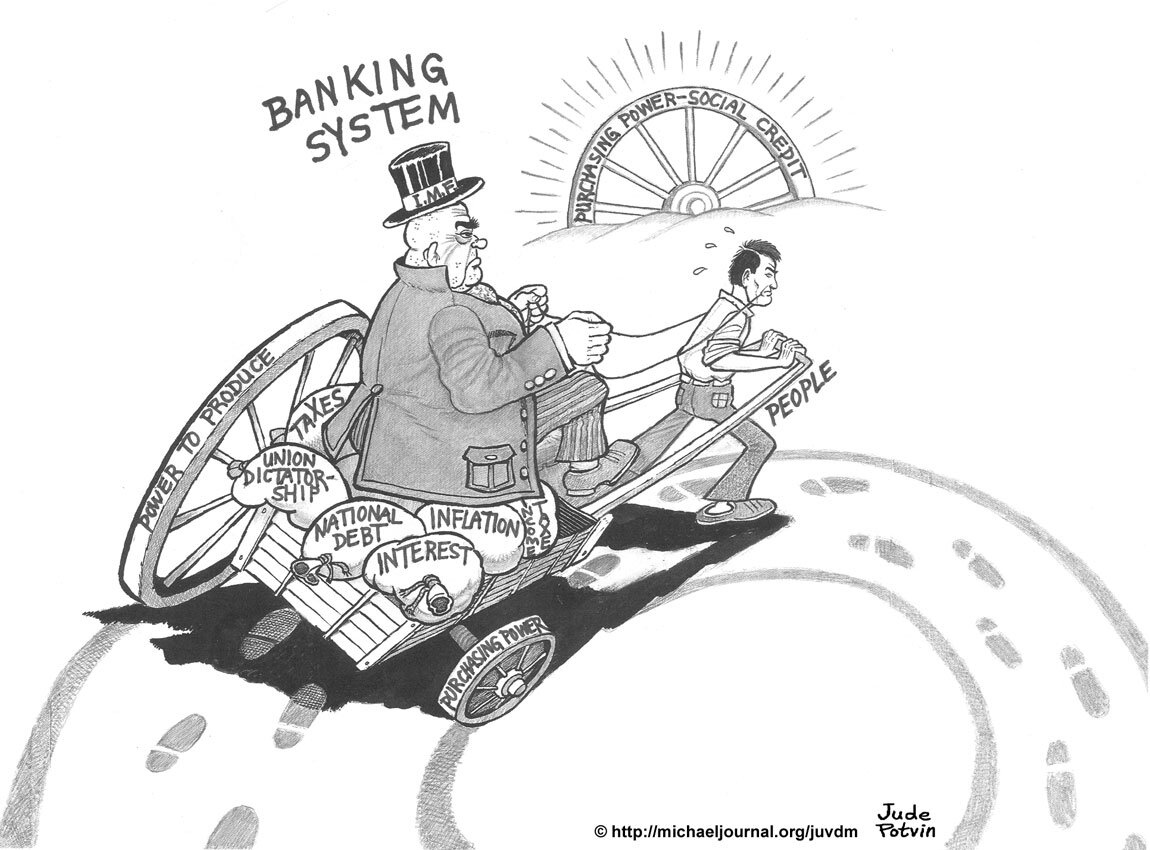

The economics of Social Credit is based on the premise that there is, under existing financial arrangements, a chronic deficiency of proper or real consumer purchasing power in the economy relative to the prices that businesses are obligated to charge in order to remain solvent.If this is the fundamental cause of the economic disease, what are its various symptoms?Social Credit theorists have, beginning with C.H. Douglas, traced the effects of the systemic lack of consumer buying power in conjunction with the methods that the current system employs in an attempt to compensate for it. Such an analysis reveals that there is not a single social problem, be it economic, societal, cultural, political, environmental, or international, that is not either caused or at least exacerbated by this elementary flaw in our financial affairs.Just as a condition of homeostasis or balance in the body is a necessary condition for human health, an endogenous financial homeostasis, or an automatic, self-liquidating balance between the flow of consumer prices and the flow of consumer incomes, is a necessary condition for economic and social well-being. The absence of any such equilibrium under the existing economic system is the driving force, the entropic principle, behind much economic and social dysfunction. To be sure, various palliatives are relied on in an attempt to restore and maintain some kind of balance, but these are akin to ineffective medicines which, instead of getting at the root causes of a problem, merely treat some of the symptoms. Like those medicines, the use of conventional financial palliatives entails risks, burdens, and side effects. While allowing the economy to hobble along, they intensify the danger and the potential fallout of a crash and generate their own manifestations of dysfunction by way of misdirecting economic activity and wasting energy and resources.The web lines of disorder run long and deep in every possible direction. By briefly cataloguing the conventional methods of economic management in conjunction with their effects on economic function, we may hope to give some indication as to the nature and extent of the malady. As we proceed, it should become increasingly obvious that Social Credit theory offers a cogent set of explanations for both the whys and the hows of our economic and social discontents.

Conventional Methods of Economic Management

If, given any specified production programme, insufficient consumer income will be distributed in the course of manufacture or delivery to offset the corresponding costs, an equilibrium between prices and incomes must be attained or at least approximated by some other means.The two basic methods under the existing financial system for bridging the macroeconomic gap between consumer prices and consumer incomes involve: 1) finding some way of lowering prices and 2) finding some way of increasing the flow of consumer purchasing power. While it is typical for both methods to be employed simultaneously, it is preferable, since the long-term survival and continued growth of the economy will depend on it, for as much of the gap as possible to be filled by adding to the flow of consumer buying power.[note]It is important to realize that even when an equilibrium between the rate of flow of consumer incomes and the rate of flow of consumer prices can be achieved by means of additional debt, this equilibrium is never a self-liquidating equilibrium. The cost of compensatory debt will appear in future prices, taxes, and debt-servicing bills; that is, the compensatory debt does not enable past costs to be eliminated once and for all, it merely shifts the obligation to pay them to a future point in time. Furthermore, even then it remains the case that total prices, or the rate of flow of aggregate prices (as opposed to the prices of consumer goods and services), will exceed the rate of flow of aggregate incomes. The disparity in the rate of flow between prices and incomes highlighted by Douglas’ A+B theorem is always operative, even if its effects at the level of consumer goods and services may be temporarily masked.[/note]Lowering prices involves having the producer subsidize the consumer out of his own financial resources. Bankruptcies oblige companies to liquidate their inventories and the reduced prices mean that consumers can purchase needed items with less money. In less severe cases, pressure can be put on firms to lower their prices to the consumer temporarily by relying on their own reserves of financial capital to meet costs that would otherwise be unrecoverable.Filling the gap by expanding the money supply, on the other hand, involves the contraction of additional debt, newly created by the private banking system in the form of intangible numbers, on the part of governments, businesses, and consumers.When governments borrow money from private banks by selling securities, the additional money is used to make up for the deficit between government expenses and taxation revenues. When such compensatory money is spent on production that the consumer does not buy (or at least will not pay for in the same period of time, but much later, if at all), things such as hospitals, schools, airports, harbours, bridges, electrical infrastructure, power plants, or public services, etc., the jobs that are thereby created (or merely maintained) distribute additional purchasing power to the population that can and will be used to obtain a greater proportion of the regular flow of consumer goods and services. Public debt expended on the provision of welfare, unemployment, or pension payments or consumer tax rebates would have the same effect, as would the use of such monies to subsidize or nationalize various industries. Of particular concern here is the use of government borrowings to maintain or expand war production, such as armaments and the regular operation of the armed forces. This likewise distributes incomes without adding to the flow of consumable goods and services.As an alternative to relying on public authorities at the various levels (whether federal, provincial or state, or municipal) to maintain sufficient air in the economic balloon by steadily augmenting the public debt, businesses can be forced or encouraged to borrow additional debt-money from the private banks in order to expand existing production or to initiate new production. So long as the goods can be sold at some intermediate or more distant point in the future (as would be the case with capital goods) with or without the magic of advertising, or, best of all, exported as part of a ‘favourable balance of trade’, the money necessary to finance such production will be forthcoming. Once again, consumer incomes, in the form of the wages and salaries of the workers and management of these various businesses, will be added to the flow of consumer buying power, without adding, in the same period of time or ever at all (as is the case with an export surplus) to the flow of consumer goods and services.Finally, beyond governmental and business attempts to add to the flow of consumer incomes via new production, the flow of consumer purchasing power can be increased by getting consumers to borrow additional debt-money directly from the banks themselves. Money created for mortgages, car loans, education loans, lines of credit, credit cards, installment purchases, etc., enables a greater proportion of goods and services to be purchased in the present at the cost of mortgaging future incomes.[note]Perhaps it should be emphasized again, especially for the benefit of newcomers to Social Credit, that banks are not mere intermediaries between borrowers and savers; they are, instead, creators and destroyers of credit. Every bank loan and bank purchase of a security creates a deposit and every repayment of a bank loan or selling of a bank-held security destroys credit. When a consumer obtains a loan from a bank, the consumer is not borrowing money from savers (other consumers), but is borrowing new money into existence in the form of bank credit.[/note]

An Evaluation of the Conventional Methods of Economic Management

In sober truth, there is not a single economic or social problem, in the broadest sense of the term ‘social’, that is not somehow tied up with this recurrent disequilibrium between the flow of prices on the one hand and the flow of incomes on the other. It is therefore impossible in the course of an article to provide the reader with a survey that would incorporate, in sufficient breadth and depth, all of the manifestations of the fallout.[note]Readers who are keenly interested in this aspect of the Social Credit analysis should read Part Two (pages 231-341) of my 548 paged tome, Social Credit Economics.[/note] In what follows, I will merely attempt to outline some of its more salient features.On a purely economic level, filling the gap with more debt-money (whenever it is successfully filled in full, thus staving off recessions or worse) is inflationary.[note]The boom-bust cycle, with all the damage and heartache it can cause alongside the potential it offers skillful business people to get rich quickly, is very largely a financial rather than a real economic phenomenon.[/note] If the economy is bustling and the banks overshoot the gap with their compensatory lending activities, sure, there can be demand inflation, but even when demand inflation is not at play there is always cost-push inflation. Additional government and business production tends to increase in taxes and prices the costs that the consumer is supposed to meet, while consumer debt will decrease future incomes in debt repayments. In both cases, a demand for wage and salary increases, to keep up with the cost of living, will arise, and these, once granted, will tend to increase prices even further. Unless they involve a more equitable distribution of profits, employers will have to borrow more money from the banks in order to meet the demand for wage and salary increases, but this will eventually necessitate an increase in prices in order to meet the increase in labour costs.[note]This wage-cost spiral induced by the reliance on additional debt to fill the price-income gap is what is responsible for the tremendous loss of purchasing power exhibited by every major currency in the last 100 years. In the United States, for example, the dollar has lost over 95% of its value since 1913.[/note] Relying on debt to fill the gap also creates an ever-growing burden of outstanding public, business, and personal debt that hangs like a noose around our collective neck. The total societal debt in the United States, for example, is somewhere on the order of 66.5 trillion, is steadily increasing, and is unrepayable.[note]Cf. www.usdebtclock.org[/note] At various points in time, the payments necessary to service these debts become too burdensome and the various economic agents are loathe to borrow any more. We then experience a credit crunch and a financial crisis in which some of the debt burden gets wiped out, thus enabling a return to lending and a more prosperous economic climate.Making the full distribution of desired production dependent in part on additional production, whether public or private (aka economic growth), and on consumer indebtedness also means that many things will have to be produced that the consumer does not want or would not want if he were adequately financed, ab initio, to buy in full whatever he produced. Whether we talk about armaments for export, or convenience foods, or daycare centres, or expanding government bureaucracy, much production is, from the point of view of the sovereign and economically independent consumer, useless, witless, redundant, and/or destructive. These forms of economic activity are deemed necessary because they distribute incomes and/or because the policy of full employment has made them necessary (they make the ‘having to go to work’ possible or easier). Such a tremendous misdirection of economic resources and effort for artificial financial reasons also entails a tremendous waste of material and human resources.Not only does the existing economic system fail, under the influence of the recurring price-income gap, to either produce or distribute everything that consumers need to survive and flourish (poverty and even destitution continue to plague modern, industrialized economies even though the goods to alleviate these conditions exist or could easily be produced) while producing many things that the consumer would not independently sanction, it also demands an inordinate amount of time and energy (often under considerable and unnecessary psychological stress) from people in the form of labour. In other words, economic inefficiency is the flipside of economic inefficacy. Since everything must be earned (or taken from those who do have jobs/investments) according to the existing economic conventions, and since the financial system does not provide workers, management, or capital (considered as the collective ‘factors of production’) with sufficient income to offset the cost-prices of their production, people in economic need have to look for jobs, any type of job, probably a job producing something witless, useless, redundant and/or destructive, in order to obtain the money to buy the food, clothes, and shelter that is already available. It would be far less wasteful if the State simply wrote a cheque to itself to make up for the lack of income and distributed it to those in need of work as a free gift.[note]We will revisit this issue in next month’s article when we will examine Social Credit’s proposed solutions.[/note] Note as well that the misdirected labour is in no way required, physically, to produce the goods and services that form a part of basic provisioning. Mandating that people must work even when the work is not physically necessary, i.e., insisting on an anachronous policy of full employment in the face of industrial productivity, is to impose a policy of servility in place of freedom in the form of leisure.At any rate, the chief beneficiaries of the conventional methods of economic management are, of course, the banks. The compensatory loans they issue allow for the centralization of wealth, power, and privilege in fewer and fewer hands. What has in effect happened is that the banks, by filling the gap with debt-money issued on asymmetrical terms, have usurped the unearned increment of economic association and have placed themselves in a position of ownership over the economy as a whole.But the purely or primarily economic consequences of the reigning economic regime are not confined to that level of human activity; they also entail innumerable ripple effects of a social, cultural, political, environmental, and international nature.To briefly survey the first three categories, family troubles, divorce, delinquency, and abortion, alcohol abuse, drugs, and crime, physical and psychological illnesses of every type, mass migration and the problems it poses for indigenous and organically derived cultures, political instability and creeping totalitarianism with its concomitant loss of liberty, etc., etc., are often either directly caused or at least exacerbated by the artificial financial pressures under which we live, move, and have our being.Quite clearly, there is also a tight connection between all of the additional production and consumption that is necessary to make a financially unbalanced economy work and environmental damage. Artificial financial restrictions in conjunction with the obsessive need for continued growth render pollution reduction, habitat preservation, and the conservation of renewable and non-renewable resources impracticable. The environment is routinely sacrificed on the altar of financial necessity.Finally, the Social Credit analysis points out that just as it is as advantageous for every country to have a ‘favourable balance of trade’ as it is impossible, the economic competition between countries for money in international markets is the driving force behind much military conflict and war.[note]International trade is a zero sum game. For every country that exports more than it imports, and is thus enabled to make up for part of its internal lack of purchasing power, there must be a country that imports more than it exports (which it probably does on credit). It is impossible for all countries to be winners.[/note] In the case of a war, missiles, bombs, and other forms of war production will be exported to the enemy.... Undoubtedly, the need to replace them will keep the domestic economy humming along. To paraphrase Orwell, (military) war is (economic) peace.

Relying on debt to fill the gap also creates an ever-growing burden of outstanding public, business, and personal debt that hangs like a noose around our collective neck. The total societal debt in the United States, for example, is somewhere on the order of 66.5 trillion, is steadily increasing, and is unrepayable.[note]Cf. www.usdebtclock.org[/note] At various points in time, the payments necessary to service these debts become too burdensome and the various economic agents are loathe to borrow any more. We then experience a credit crunch and a financial crisis in which some of the debt burden gets wiped out, thus enabling a return to lending and a more prosperous economic climate.Making the full distribution of desired production dependent in part on additional production, whether public or private (aka economic growth), and on consumer indebtedness also means that many things will have to be produced that the consumer does not want or would not want if he were adequately financed, ab initio, to buy in full whatever he produced. Whether we talk about armaments for export, or convenience foods, or daycare centres, or expanding government bureaucracy, much production is, from the point of view of the sovereign and economically independent consumer, useless, witless, redundant, and/or destructive. These forms of economic activity are deemed necessary because they distribute incomes and/or because the policy of full employment has made them necessary (they make the ‘having to go to work’ possible or easier). Such a tremendous misdirection of economic resources and effort for artificial financial reasons also entails a tremendous waste of material and human resources.Not only does the existing economic system fail, under the influence of the recurring price-income gap, to either produce or distribute everything that consumers need to survive and flourish (poverty and even destitution continue to plague modern, industrialized economies even though the goods to alleviate these conditions exist or could easily be produced) while producing many things that the consumer would not independently sanction, it also demands an inordinate amount of time and energy (often under considerable and unnecessary psychological stress) from people in the form of labour. In other words, economic inefficiency is the flipside of economic inefficacy. Since everything must be earned (or taken from those who do have jobs/investments) according to the existing economic conventions, and since the financial system does not provide workers, management, or capital (considered as the collective ‘factors of production’) with sufficient income to offset the cost-prices of their production, people in economic need have to look for jobs, any type of job, probably a job producing something witless, useless, redundant and/or destructive, in order to obtain the money to buy the food, clothes, and shelter that is already available. It would be far less wasteful if the State simply wrote a cheque to itself to make up for the lack of income and distributed it to those in need of work as a free gift.[note]We will revisit this issue in next month’s article when we will examine Social Credit’s proposed solutions.[/note] Note as well that the misdirected labour is in no way required, physically, to produce the goods and services that form a part of basic provisioning. Mandating that people must work even when the work is not physically necessary, i.e., insisting on an anachronous policy of full employment in the face of industrial productivity, is to impose a policy of servility in place of freedom in the form of leisure.At any rate, the chief beneficiaries of the conventional methods of economic management are, of course, the banks. The compensatory loans they issue allow for the centralization of wealth, power, and privilege in fewer and fewer hands. What has in effect happened is that the banks, by filling the gap with debt-money issued on asymmetrical terms, have usurped the unearned increment of economic association and have placed themselves in a position of ownership over the economy as a whole.But the purely or primarily economic consequences of the reigning economic regime are not confined to that level of human activity; they also entail innumerable ripple effects of a social, cultural, political, environmental, and international nature.To briefly survey the first three categories, family troubles, divorce, delinquency, and abortion, alcohol abuse, drugs, and crime, physical and psychological illnesses of every type, mass migration and the problems it poses for indigenous and organically derived cultures, political instability and creeping totalitarianism with its concomitant loss of liberty, etc., etc., are often either directly caused or at least exacerbated by the artificial financial pressures under which we live, move, and have our being.Quite clearly, there is also a tight connection between all of the additional production and consumption that is necessary to make a financially unbalanced economy work and environmental damage. Artificial financial restrictions in conjunction with the obsessive need for continued growth render pollution reduction, habitat preservation, and the conservation of renewable and non-renewable resources impracticable. The environment is routinely sacrificed on the altar of financial necessity.Finally, the Social Credit analysis points out that just as it is as advantageous for every country to have a ‘favourable balance of trade’ as it is impossible, the economic competition between countries for money in international markets is the driving force behind much military conflict and war.[note]International trade is a zero sum game. For every country that exports more than it imports, and is thus enabled to make up for part of its internal lack of purchasing power, there must be a country that imports more than it exports (which it probably does on credit). It is impossible for all countries to be winners.[/note] In the case of a war, missiles, bombs, and other forms of war production will be exported to the enemy.... Undoubtedly, the need to replace them will keep the domestic economy humming along. To paraphrase Orwell, (military) war is (economic) peace.